Implicit Language Policies in Social Movements and Beyond

By Ganesh Birajdar

Just as it is impossible to claim to be an expert on languages of South Asia, the social movements of South Asia are equally an enormous topic. I therefore have mustered up all my courage and gathered my own reflections from my limited experience, to write about implicit language policies within South Asian movements. But here I will give it a shot, and consider this just an introduction. In order to understand the complexity of social movements and language in South Asia, we would need a contribution from someone from each and every social movement!

Now to speak about the spaces that I have been in, I notice that language has been seen as a tool of communication rather than a tool of inclusion or a tool to dismantle power. The choice of language is often made as a matter of convenience and issues of representation are not always considered.

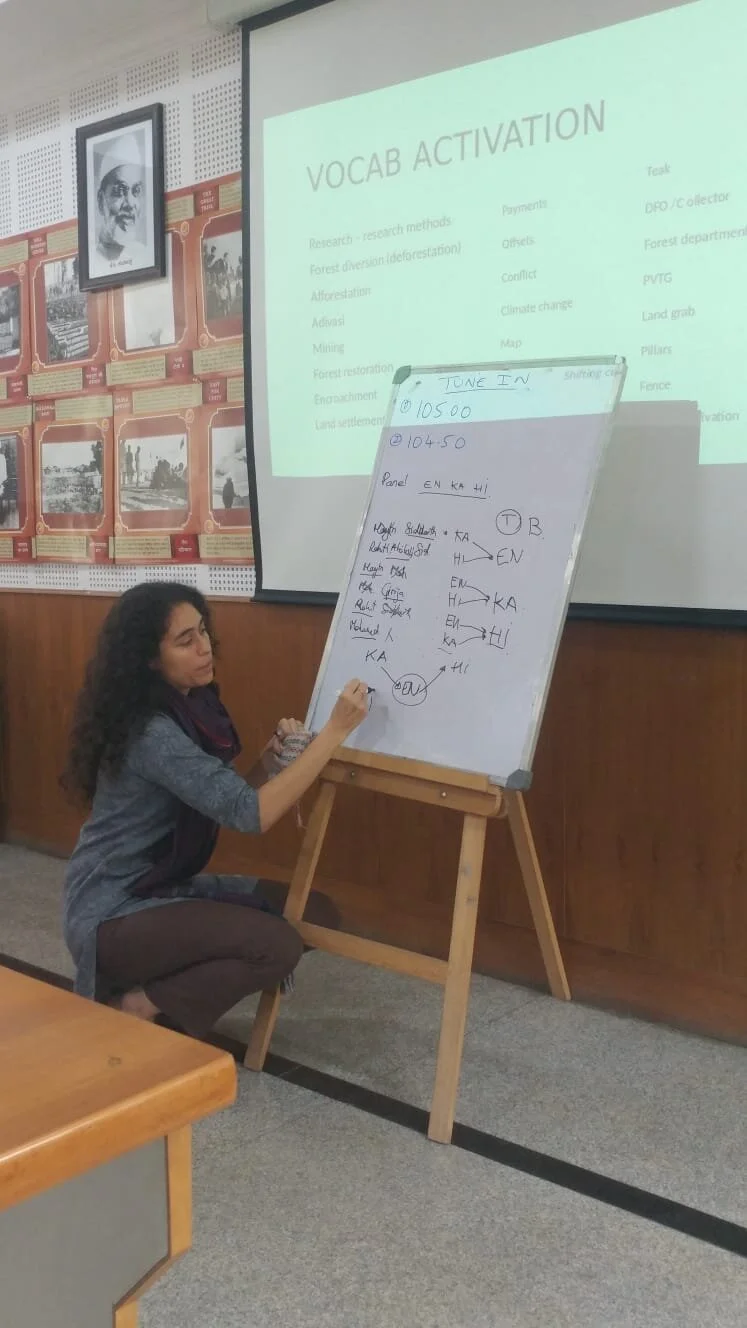

SASI member Susana shows workshop participants how to plan for a multilingual event, 2019

There is a pattern in the choice of the language for different aspects of work in movements. Regional languages are used only when representation or an implementation of decisions is needed, while English/Hindi are often used to take high-level decisions or convey reports. It is common within our national organizations to find research and policy papers in English, while booklets, slogans and hoardings will be in native languages. So, on the one hand, English/Hindi as a language of research and report-writing is often considered the common language of work, as it is easy to share with peers from other movements/organizations. This allows those who have these linguistic skills to automatically become the representatives of the voices of the people within the given organizations.

It is a highly undisputed reality that (even within social movements) people who speak English take on leadership roles, especially those that need interorganizational communication. As ideas of language justice are not in the picture, and nor is interpretation, English speakers are assumed and entitled towards these positions. This especially excludes women and youth.

I became conscious about the importance of interpretation and its impact on the representation of voices in movements for the first time when I came in contact with La Via Campesina South Asia. I had been part of discussions in many social groups, NGOs and movement spaces for 7-8 years prior to this, mostly in Maharashtra, India, but I had never attended a meeting in which the need of interpretation was acknowledged and fulfilled. Until this moment, I simply had not noticed how without interpreting, we exclude people and create a language barrier.

This exists outside of movements too. In general, the present-day social, political and economic public worlds that exist in South Asia always favour dominant-language speakers. At the same time, these worlds also favour those who have had the privilege of speaking and having their voices heard at times to redundancy, for example, members of the upper caste, men, religious majorities, landlord farmers, cis-gender individuals, gender-conforming individuals, the middle-class, aristocrats or most politicians, village pradans, academics, journalists, government office workers, police officers, etc. Language accessibility and having one’s voice heard is not such a real struggle for those listed here, yet even they will benefit from language accessibility.